Sacred Spaces in Australia

Create your own gallery of Australian Sacred Spaces. Describe the numinous qualities that you experience at each site. Maybe add them to a map of our great southern land. You can download a blank map here.

While watching the video take notes on a map about the natural profile of Australia. Is Australia a naturally spiritual place?

|

Tim Winton's account of the importance of country. How does he describe his passion for this place? List his ways of expressing the sacredness of this country.

| ||||||||||||

Call of the Sacred

Margaret Smith

|

At the beginning of many gatherings we honour the Aboriginal people on whose land we stand, yet in our highly developed culture, rarely are we able to perceive the wisdom, richness and depth of traditional Aboriginal culture and spirituality, or understand their relationship with the land. Our many material advantages have taken us on a path away from the bodily sense of the sacred, which is experienced through to nature and reveals our interconnectedness with it.

We are only dimly aware of the numinous quality of this ancient land we inhabit. We know its beauty, but rarely do we recognise this appreciation as the call to the deeper experience of sensing the sacred presence within the land that is sometimes felt as a tangible silence. Awareness of this sacred presence was the milieu in which traditional Aboriginal culture and spirituality developed its relationship to the land, and drew its wisdom and depth. Some comparisons with the ancient roots of the Christian tradition indicate that the ancient Israelites, the Aramaic speaking people of the Middle East and the Celts all experienced a numinous presence in the earth, in nature and the cosmos, and felt a mystical interconnection with the natural world through this immanent presence. This experience gave depth and richness to their spirituality, and respect for the land in which they lived. Though the cultures and settings are entirely different, their experience had marked similarity to the experience of the numinous presence in the land that gave rise to the spirituality and mystical relationship with the land that Aboriginal people still retain. Aboriginal people learned over thousands of years to respond to the numinous quality which they sensed emanated from the land and they felt themselves to be in relationship with the land through this sacred presence. They described this relationship in the Dreamtime stories, which told of the continued presence and activity in the land of the Dreamtime Beings who had originally created it. These beings of the Dreaming made known the laws for care of the land that ensured its on-going fertility and the well being of the people. An essential part of the care of land and people was the sacred song and dance that celebrated the journeys and creation activities of the Dreamtime Beings and was passed down through the generations. In a similar way Israel passed down her spiritual heritage through myth, story and psalms recorded in the Bible for the continuing guidance of the people. The Aboriginal people’s recognition of their divinely given responsibility to care for the land in a relationship of mutual benefit had its counterpart in the ancient Israelites’ recognition of their covenantal responsibility to live and tend their flocks in the land they were given, so as to benefit from its milk and honey. The people of the Middle Eastern Aramaic speaking world to which Jesus belonged were close to the earth, and experienced a sense of numinous interconnection with the entire universe, not unlike that experienced by Aboriginal people in relation to the land..... It is not surprising that the Gospels speak of Jesus going to pray alone in a natural setting. Though expressed through entirely different cultures in different settings, in both the Aboriginal experience of interconnection with the land through the Dreamtime Beings, and the Aramaic experience of permeation and interconnection through the One, the division between humanity and nature was but as a thin veil. This experience was also shared by the Celts who were aware of the Divine Presence in nature, and identified this Presence that made the separation between humanity and nature so slight, as the Trinity, the three-ness (Source, Presence and Activity) and oneness (Communion) permeating all. I arise today through a mighty strength, the invocation of the Trinity, through belief in the three-ness, through confession of the oneness of the Creator of Creation... I arise today through the strength of heaven; Light of Sun, Radiance of moon, Splendour of fire, Speed of lightning, Depth of sea, Stability of earth, Firmness of Rock. (From the The Deer’s Cry otherwise known as St Patrick’s Breastplate) Adam, David. The Cry of the Deer, Triangle/SPCK, London, 1996. |

How do you hear the call of the sacred?

Defining Faith and Naming the Sacred

Creed for Australia

|

We believe

that this ancient land, with all its unique creatures, is a precious gift from a loving god, whose mercy is over all his works. We believe in god's care for aboriginal people who treasure it through unnumbered generations: the one who grieves in their suffering and rejoices in every noble aspiration. We believe in god's compassion for the patchwork of refugees who for two hundred years have come to this continent looking for a place to call their home. We believe in god's steadfast love for this nation and all its children, that god is creating a new people from many races, colours and gifts, to fulfill a high destiny. We believe that the best way forward is the way revealed by Jesus, of faith, hope and love, where no needy person is neglected and no bidding of the spirit ignored. By Bruce Prewer Highlight the elements of this creed that appeal to your sense of the sacred |

creed (krēd)n.

1. A formal statement of religious belief; a confession of faith. 2. A system of belief, principles, or opinions: laws banning discrimination on the basis of race or creed; an architectural creed that demanded simple lines. [Middle English crede, from Old English crēda, from Latin crēdō, I believe; see credo.] The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition copyright ©2000 by Houghton Mifflin Company. Updated in 2009. Published by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. http://www.thefreedictionary.com/creed |

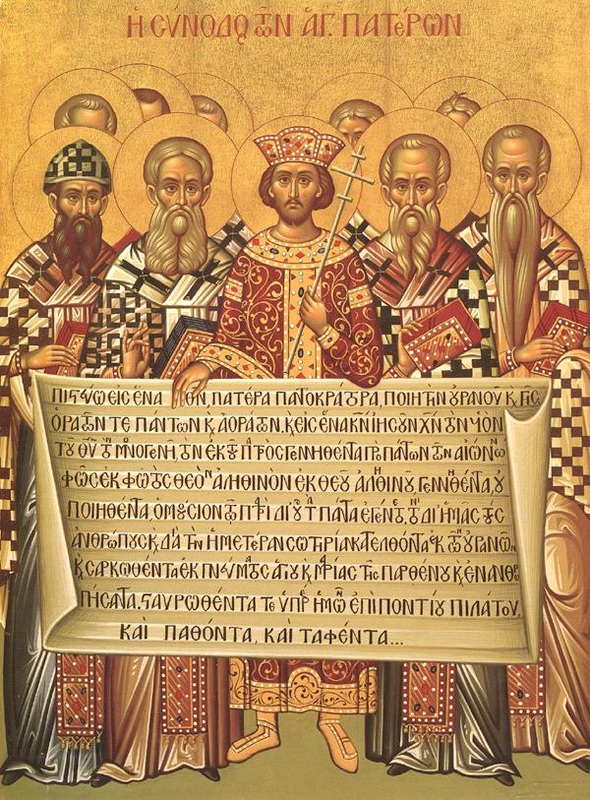

Source: http://chronicle.com/blognetwork/castingoutnines/files/2008/06/nicene-creed.png

Source: http://chronicle.com/blognetwork/castingoutnines/files/2008/06/nicene-creed.png

The Creeds of the Catholic Church

Click on the link to see these statements of faith of the Catholic Church. What is the faith that they are expressing?

Nicene Creed

Apostle's Creed

Click on the link to see these statements of faith of the Catholic Church. What is the faith that they are expressing?

Nicene Creed

Apostle's Creed

Defining Spirituality

The term 'spirituality' is French Catholic in origin and did not fully develop as a concept until the 18th Century. Giving an exact definition for the term becomes difficult. Used by the Church at many stages and in varying ways to attempt to define, explain, and outline the entire relationship between a person and God a precise definition becomes impossible. Contemporary usage in wider society complicates a definition further with the concept leaving its Christian roots behind and coming to mean any aspect of humanities connection to something other than itself. This includes deism (natural revelation), and theism (revealed revelation), yet also expands to include even other human relationships. Spirituality in its broadest sense is the evidence of, or attempt to explain, human transcendence.

Some have sought to argue that religion refers to an institutional dimension whereas spirituality is to do with more subjective personal perspectives (Hill and Pargament 2003, 64). Such distinctions are often used to paint religion in a negative light in contrast with more 'enlightened' contemporary spirituality. Of course, there can be both helpful and unhelpful religions and spiritualities. Religion can also be intensely personal (eg Wuthnow 1998) just as some contemporary spiritualities can form part of large international business complexes. Further, in practice, many experience spirituality in a religious context and do not draw such distinctions (Marler and Hadaway, 2002).

Some have sought to argue that religion refers to an institutional dimension whereas spirituality is to do with more subjective personal perspectives (Hill and Pargament 2003, 64). Such distinctions are often used to paint religion in a negative light in contrast with more 'enlightened' contemporary spirituality. Of course, there can be both helpful and unhelpful religions and spiritualities. Religion can also be intensely personal (eg Wuthnow 1998) just as some contemporary spiritualities can form part of large international business complexes. Further, in practice, many experience spirituality in a religious context and do not draw such distinctions (Marler and Hadaway, 2002).

- Hill, P.C., & Pargament, K.I., (2003). Advances in the conceptualisation and measurement of religion and spirituality: Implications for physical and mental health. American Psychologist, 58 (1), 64-74.

- Marler, P.L., & Hadaway, C.K., (2002). "Being religious" or "being spiritual" in America: A zero-sum proposition? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 41, 289-300.

- Wuthnow, R. (1998). After heaven: Spirituality in America since the 1950s. Berkeley: University of California Press.

|

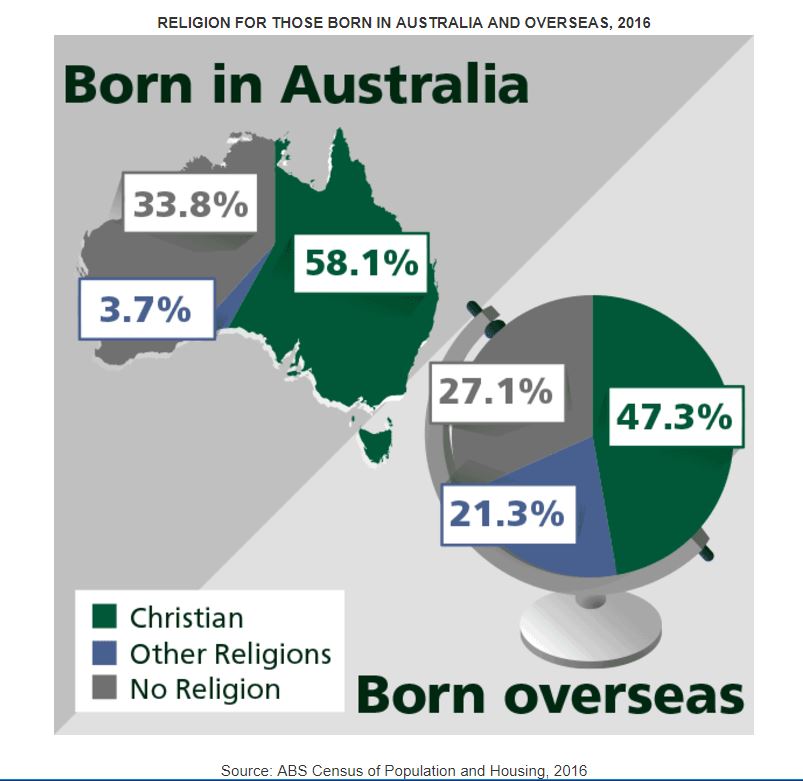

How ‘Christian’ are Australians?

How 'Christian' are Australians? How much confidence do they have in the churches and what do they see as the role of churches in our multi-faith society? Six out of ten Australians affiliate themselves with one of the Christian churches. Most Australians have some contact with the churches and see them as having a wider role, primarily as moral guardians, but also to provide public worship and a range of social services. There is no doubt that there have been changes in the place of Christian churches in the past few decades, yet they remain a significant part of the Australian landscape. Source: http://www.ncls.org.au/default.aspx?sitemapid=26 |