Types of Rituals in Society |

| ||||||

Personal Rituals

There are familiar rituals in everyone's lives. There may be a ritual to the way people usually spend their lunch times, perhaps going to a certain place everyday, or having the same kinds of food regularly. There may be a sequence of things that a student does when he or she returns from school every day. In a certain way, these can be called rituals because they are done regularly, in more or less the same order. This is one sense in which the word ritual is used. It can describe an action or series of actions that tend to be done in the same way over and over again.

Social Rituals

The word 'ritual' is also used about social gatherings. When family or friends visit for a special occasion such as a birthday or Christmas, certain things are done, often in the same way year after year. Greetings are exchanged, gifts are given, a meal is shared. Each of these actions has a special meaning for the people who are involved. Together they make up what could be called family rituals or social rituals. These family or social rituals have an important role in the development of self-esteem, a sense of identity, a sense of belonging for those who participate in them.

Community Rituals

Often communities have special rituals that express and celebrate who they are as a community. One community ritual in Melbourne is the annual Moomba parade. Other Australian cities, or groups within these cities, have their own community rituals. The Moomba festival has been held in Melbourne every year since 1955. The festival takes place annually in March and lasts for 11 days. The Moomba parade which is its central action, is led through brightly decorated streets by a King of Moomba, who has been especially chosen for the occasion. The parade includes bands, clowns, marchers and other entertainers, and is a community ritual that is very well known to the people of Melbourne. To the extent that it helps the community to think of themselves as a community, and to celebrate together, it has an important role in contributing to collective identity of the people of Melbourne.

Religious Rituals

Rituals are very important in religion. A religious ritual may be defined as:

The repetition of an ordered special kind of behaviour, particularly relating to the religious beliefs of a community.

In fact, the essence of a ritual is that it expresses the beliefs, hopes and personal experiences of the members of that community.

Rites of Passage

Rites of Passage are a particular kind of religious ritual. They mark the transition from one stage or way of life to another. They often express and celebrate important times in the life journey of the individual or the community, and have a special role to play in the development of the person's sense of self. Rites of passage may be

There are familiar rituals in everyone's lives. There may be a ritual to the way people usually spend their lunch times, perhaps going to a certain place everyday, or having the same kinds of food regularly. There may be a sequence of things that a student does when he or she returns from school every day. In a certain way, these can be called rituals because they are done regularly, in more or less the same order. This is one sense in which the word ritual is used. It can describe an action or series of actions that tend to be done in the same way over and over again.

Social Rituals

The word 'ritual' is also used about social gatherings. When family or friends visit for a special occasion such as a birthday or Christmas, certain things are done, often in the same way year after year. Greetings are exchanged, gifts are given, a meal is shared. Each of these actions has a special meaning for the people who are involved. Together they make up what could be called family rituals or social rituals. These family or social rituals have an important role in the development of self-esteem, a sense of identity, a sense of belonging for those who participate in them.

Community Rituals

Often communities have special rituals that express and celebrate who they are as a community. One community ritual in Melbourne is the annual Moomba parade. Other Australian cities, or groups within these cities, have their own community rituals. The Moomba festival has been held in Melbourne every year since 1955. The festival takes place annually in March and lasts for 11 days. The Moomba parade which is its central action, is led through brightly decorated streets by a King of Moomba, who has been especially chosen for the occasion. The parade includes bands, clowns, marchers and other entertainers, and is a community ritual that is very well known to the people of Melbourne. To the extent that it helps the community to think of themselves as a community, and to celebrate together, it has an important role in contributing to collective identity of the people of Melbourne.

Religious Rituals

Rituals are very important in religion. A religious ritual may be defined as:

The repetition of an ordered special kind of behaviour, particularly relating to the religious beliefs of a community.

In fact, the essence of a ritual is that it expresses the beliefs, hopes and personal experiences of the members of that community.

Rites of Passage

Rites of Passage are a particular kind of religious ritual. They mark the transition from one stage or way of life to another. They often express and celebrate important times in the life journey of the individual or the community, and have a special role to play in the development of the person's sense of self. Rites of passage may be

- birth rituals such as Baptism, or naming ceremonies;

- puberty rituals such as rites as Bar Mitzvah,

- tribal initiation rituals;

- marriage rituals;

- death rituals such as requiem services and funerals;

- special office rituals such as Coronations, Ordinations.

|

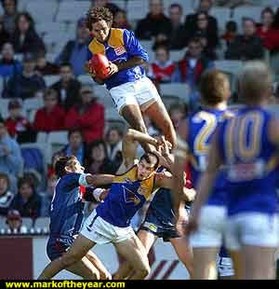

RITUAL OF PARTICIPATION

By Frank O'Loughlin Football is a 'ritual', a ritual based on the relationship between the playing of this game and the football supporters. This relationship is one of identification and identity: the football game is the ritual in which the supporters identify themselves as 'Collingwood' or 'Carlton'. I ask readers to excuse me as, despite my own best efforts, I have found it impossible in Melbourne to escape the influence of Australian Rules Football. |

| ||||||

It is at the Saturday or Sunday 'liturgy' that one finds 'the source and summit' of one's whole 'Collingwood' or 'Carlton' life. It is in gathering with others at the game that this identity is experienced again and again, and that the tradition received from the past is handed on and imbibed. Without the ritual, one loses one's identity. This accounts for groups of people, once called 'South Melbourne' supporters, wandering back streets of Melbourne. For these dispossessed any 'conversion' to Sydney involved a deep clash of identity!

The tradition of belonging is often a family possession or at times it may be associated with belonging to a particular place; in other instances the tradition may be passed on by contact with some significant person who is a supporter of the club, or it may arise gradually from admiration for a certain player in the team.

In each case, one is taken up into something bigger than oneself, a tradition, a social group with a sense of solidarity. This process of initiation is, as St Paul might have said, a matter of engrafting rather than simply associating oneself with the group.

The sense of identity produced by the playing out of the game often arouses very strong emotion. Team identification can cut across deeper identities at least during the game and its aftermath. Families in which different teams are followed can suffer disruption of their otherwise harmonious existence during and after the game.

Rituals which are genuine express in action the identity of a social group. Identity is something intangible yet very real; it goes into our own very making. It is revealed to us, made accessible to us in ritual or symbolic activity.

Let's look further at the dynamic of the football match. It is visible and tangible activity where physical energy radiates and psychic / emotional energy has great power. We have a very simple activity at the visible or tangible level: there are fellows (usually) kicking a ball about the field seeking to get it through the goalposts. This activity has a triggering effect on the crowd: every time a Collingwood player kicks a goal, the Collingwood crowd takes it to itself as being its own. What the Collingwood players do is seen by the supporters as done for them, as done in their name. This is Collingwood's goal! There is an identification between players and the crowd. The identity of being Collingwood' is expressed and imbibed.

The game is a different reality for the Collingwood supporter than it is for the admirer of football skills. Identification is the fulcrum of the whole activity as a ritual. It brings into play other things, like the human need for solidarity, pride in one's own 'kind' (or tribe), the desire to excel... It is in playing out the football match that these further dimensions of its own reality are revealed. (This could almost be a definition of mystery, one of the original terms used to describe the sacraments.)

It is the very dynamic of the game itself that sets in motion the sense of identity between the supporters and the team, rather than any explicit intention of the participant. The game triggers it all, sets it off, for the participant who has a basic identification with the team to begin with. That is, the ritual works ex opere operato. The football match is a ritual in which the team, players and supporters recognise their own identity. And the football match can only be played out by use of the ball. Whatever the game itself is, it exists only in and through what is done with the ball. (It even shares the ball's name.)

Likewise the celebration of the Eucharist is the ritual or symbolic action in which the assembly recognises and takes to itself its own identity as the Church. In the Eucharist we open ourselves up to be penetrated and possessed by that identity. Our identity is in our communion with Jesus Christ. This is played out in what we do with bread and wine.

The tradition of belonging is often a family possession or at times it may be associated with belonging to a particular place; in other instances the tradition may be passed on by contact with some significant person who is a supporter of the club, or it may arise gradually from admiration for a certain player in the team.

In each case, one is taken up into something bigger than oneself, a tradition, a social group with a sense of solidarity. This process of initiation is, as St Paul might have said, a matter of engrafting rather than simply associating oneself with the group.

The sense of identity produced by the playing out of the game often arouses very strong emotion. Team identification can cut across deeper identities at least during the game and its aftermath. Families in which different teams are followed can suffer disruption of their otherwise harmonious existence during and after the game.

Rituals which are genuine express in action the identity of a social group. Identity is something intangible yet very real; it goes into our own very making. It is revealed to us, made accessible to us in ritual or symbolic activity.

Let's look further at the dynamic of the football match. It is visible and tangible activity where physical energy radiates and psychic / emotional energy has great power. We have a very simple activity at the visible or tangible level: there are fellows (usually) kicking a ball about the field seeking to get it through the goalposts. This activity has a triggering effect on the crowd: every time a Collingwood player kicks a goal, the Collingwood crowd takes it to itself as being its own. What the Collingwood players do is seen by the supporters as done for them, as done in their name. This is Collingwood's goal! There is an identification between players and the crowd. The identity of being Collingwood' is expressed and imbibed.

The game is a different reality for the Collingwood supporter than it is for the admirer of football skills. Identification is the fulcrum of the whole activity as a ritual. It brings into play other things, like the human need for solidarity, pride in one's own 'kind' (or tribe), the desire to excel... It is in playing out the football match that these further dimensions of its own reality are revealed. (This could almost be a definition of mystery, one of the original terms used to describe the sacraments.)

It is the very dynamic of the game itself that sets in motion the sense of identity between the supporters and the team, rather than any explicit intention of the participant. The game triggers it all, sets it off, for the participant who has a basic identification with the team to begin with. That is, the ritual works ex opere operato. The football match is a ritual in which the team, players and supporters recognise their own identity. And the football match can only be played out by use of the ball. Whatever the game itself is, it exists only in and through what is done with the ball. (It even shares the ball's name.)

Likewise the celebration of the Eucharist is the ritual or symbolic action in which the assembly recognises and takes to itself its own identity as the Church. In the Eucharist we open ourselves up to be penetrated and possessed by that identity. Our identity is in our communion with Jesus Christ. This is played out in what we do with bread and wine.