Challenges and responses

Each religion has a story to tell. Each story is a journey comprising moments of glory, peace, war, aggression, introspection and reflection. These events, some of which are significantly challenging, are characterised by attitudes, actions, strategies, policies, methods and stances that are inspired by hope or fear; hostility or amelioration; disillusionment or commitment; arrogance or humility; self-interest or mercy; generosity or greed. Religions do not arrive in human society as fully developed belief communities or institution s; they grow over time. This growth is uneven, sometimes rapid and at other times gradual or static.

Since this area of study is deals with the full extent of the history of the faith system being studied, this brief history of the Roman Catholic Church provides students with the background knowledge to the types of challenges faced by religious traditions and the stances that it has taken. This historical overview helps students keep in mind the fluid and dynamic nature of the Church, the social milieu in which it has existed, the challenges that it has faced, the stances that it has taken and its response to various challenges. Whilst there have been many historical events within and outside the Church which have challenged its beliefs, ethics and its very existence, only some of the more significant ones are included here in this summary. The nature of what makes a challenge significant is also a feature of this study.

Since this area of study is deals with the full extent of the history of the faith system being studied, this brief history of the Roman Catholic Church provides students with the background knowledge to the types of challenges faced by religious traditions and the stances that it has taken. This historical overview helps students keep in mind the fluid and dynamic nature of the Church, the social milieu in which it has existed, the challenges that it has faced, the stances that it has taken and its response to various challenges. Whilst there have been many historical events within and outside the Church which have challenged its beliefs, ethics and its very existence, only some of the more significant ones are included here in this summary. The nature of what makes a challenge significant is also a feature of this study.

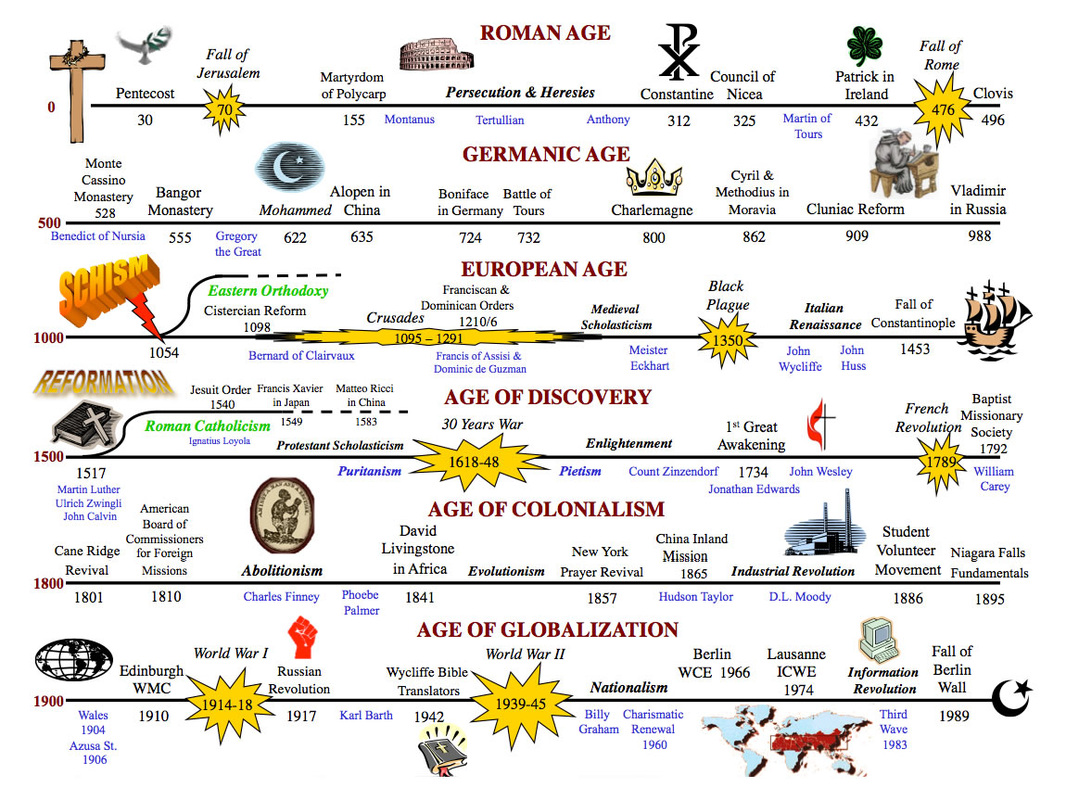

30-70 AD The Time of Jesus and the Apostles

70-312 The Age of Emerging Christianity

312-497 The Age of the Christian Empire

476-1517 The Middle Ages

1517-1648 The Age of Reformation / Counter Reformation

1648-1789 The Age of Reason and Revival

1789-1914 The Age of Progress

1914-1965 The Age of World Wars

30CE – 70CE The Time of Jesus and the Apostles

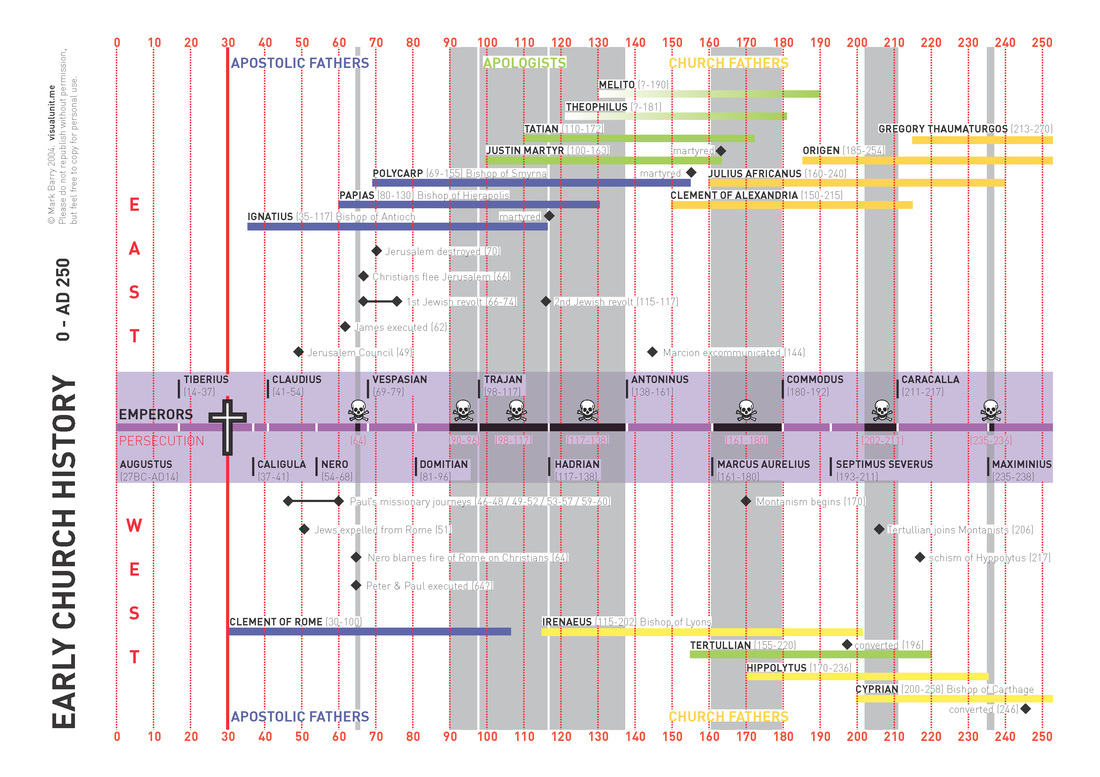

Since Jesus was a Jew and his message was directed towards the people of Israel, Christianity naturally arose within the Jewish community living under the reign of the Roman Empire. Very soon, however, it began to spread into the Gentile (non‑Jewish) populations, thanks largely to the missionary zeal of one extraordinary man: Paul of Tarsus. Paul braved shipwreck, imprisonment, ridicule and eventually martyrdom in order to proclaim the Good News throughout the Graeco‑Roman world. His letters are the first contribution to what will become the Christian scriptures. Under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, the first Christians established the essential cornerstones of Church life - ekklesia. The new religion had changed in nature from the time immediately following the death of Jesus. Initially, major questions centred on the problem of the nature of the relationship between Christians and Jews, a source of great angst for those who were the first followers of Jesus. The second major issue faced by the first followers was the fact that Jesus' second coming had not occurred, when initially they believed that the end-times and their salvation were imminent. The destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE was not inconsequential for the eventual separation of Christianity and Judaism.

70-313CE The Age of Emerging Christianity

This era saw the emergence of the remaining New Testament scriptural writings. During the first three hundred years, Christians were often persecuted and killed by the rulers of the day who perceived the Church as a potential threat. Thus the first saints to be recognised were often martyrs. As time went on, more great teachers, thinkers and leaders were raised up, who continued to explore and consolidate the message of Christ and what it meant for Christians. We refer to these figures as the 'Church Fathers'. Often their contributions arose out of the midst of conflict, as they faced those who threatened to distort the true message of the Gospel. By the time Christianity came out into the mainstream Roman society with the Edict of Milan, the separation between Judaism and Christianity had been completed and the reality of having to wait an unknown amount of time for the second coming had been faced. Christianity had become more organized, but there was still lack of theological clarity.

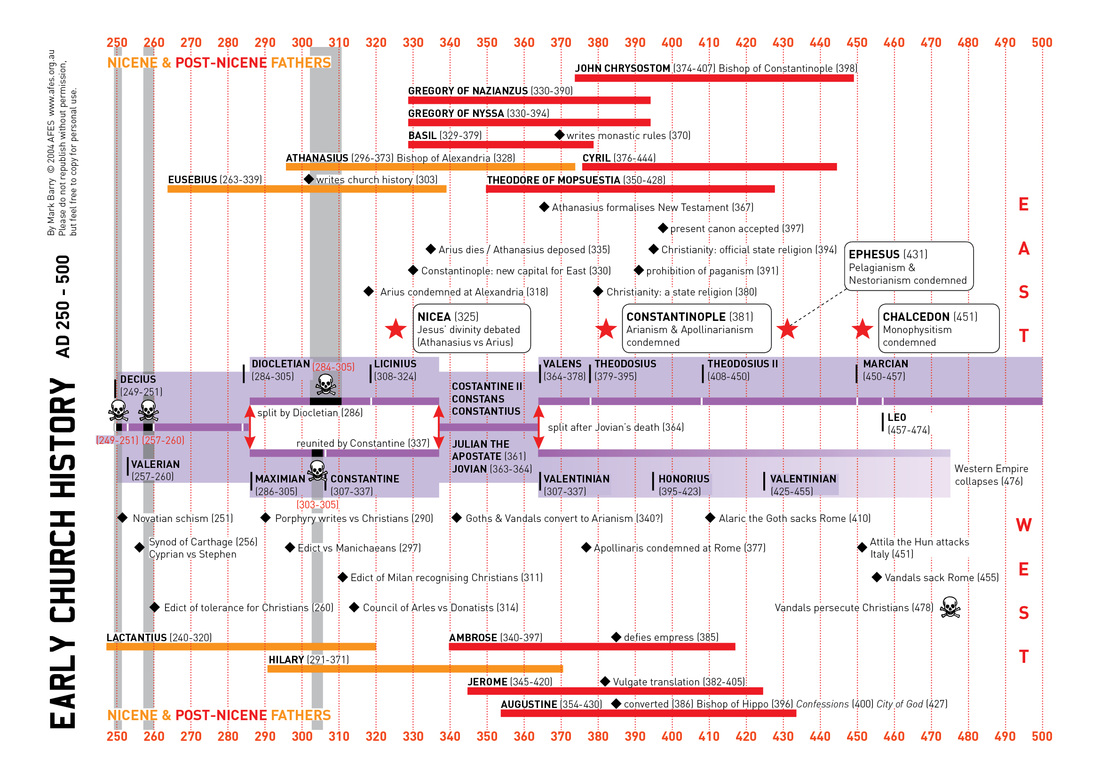

313-497CE The Age of the Christian Empire

Persecution eased in the fourth century when the Roman Emperor, Constantine himself became a Christian. Previously, gatherings were held in secret, writings were undertaken but not disseminated widely, and the fate of many who believed in Christ was death. The edict granted freedom of worship to Christians in the Roman Empire, and by the end of the century, Christianity had become the authorised religion of the Empire. Constantine moved his capital to Byzantium on the Bosphorus and renamed it Constantinople (Modern day, Istanbul). Definite patterns of worship had been developed, a hierarchy of leadership formed, and some sacramental theology delineated. The significance of this event was in the freedom to develop and blossom the young faith. Constantine called the first ecumenical council at Nicea in 325CE. The Christian Church was to make clear its beliefs about the relationship of Jesus and the Father. It was determined by the council that Christ was homoousia, meaning, one substance with the Father. Christianity grew in status and influence from this time on. Constantine ordered 50 Christian bibles (Greek Language) to be made by Eusebius of Caesarea for use on Constantinople. The Church grew in strength and influence during this time, even as the Roman Empire itself began to decline. The Western Churches consolidated under the Bishop of Rome and spoke Latin, and the Eastern Churches had their prestigious capital in Constantinople and spoke Greek.

476-1517 The Middle Ages

There were a series of disagreements between East and West in the centuries after the fall of Rome. The pope’s prestige was often in question, but popes often found ways to remain prominent. The Church expanded its own empire into such far-flung places as Ireland, Scotland, Moravia and Romania. In 800CE, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne Emperor of the Romans on December 25 at St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. The rise of Islam would become an ongoing threat to the Christians of East and West in ensuing centuries. The importance of the Bishop of Rome steadily grew, leading eventually to the enduring notion of papal primacy - the Bishop of Rome being the most important bishop in the Western Church.

In the eleventh century there was a great increase in the power of the papacy including the excommunication of the Eastern Patriarch. In 1054, Christianity was split by the East-West Schism. Western Europe emerged as a separate political and cultural unit, the Church occupying a central place in its development. Pope Urban II was preaching crusades against the Islam in 1095. Monastic life was thriving, despite the neglect of theological and spiritual matters and Church leaders behaving more often like feudal warlords.

By the fourteenth century, the power of the pope started to decline and in response, spiritual and mystical movements arose. The Church leadership was in many ways out of touch with the people and the formation of mendicant orders like the Franciscans and Dominicans was a sign of hope. The mendicants avoided owning property, did not work at a trade, and embraced a poor, often itinerant lifestyle. They depended for their survival on the goodwill of the people to whom they preached. Fear dominated the mind of the common folk. Fear of God and fear of judgment were affirmed by the Black Death, which devastated the population. Salvation was actively sought by the faithful, and people went on pilgrimages and did severe penances to prepare for eternity. For a period the papacy shifted to Avignon in France and there followed time of multiple popes, not sorted until the Council of Constance in 1415. There was a need for and calls for reform. The pomp of the church hierarchy, the moral vicissitudes of the papacy, the Italian Renaissance and humanism, as well as the invention of the Guttenberg’s printing press were all factors that contributed to that urge for reform.

1517-1648 The Age of Reformation / Counter Reformation

The Reformation was a great watershed in the life of the Church and the society of the middle ages. It determined the divisions between branches of Christianity that still exist today, and it determined the direction of the Catholic Church which was to be undertaken until the time of the next great reform of Vatican II. Martin Luther epitomises the character of the Reformation and the reformer. Through Luther’s study, he discovered that the Church in Germany had been abusing its mission by demanding money for indulgences (The Pope had been using the money to build St. Peter's Basilica in Rome). This was but one example of the exploitation that church officials were engaged in in the 16th Century. Luther, who eventually became the papal accuser, was shocked and surprised by the ensuing furor aroused by his 95 theses posted on the door of the canon church in Wittenberg. His excommunication was not expected, but the level of support he eventually found led to the formation of the Lutheran Church. This reform was followed by the formation of the Reformed, Anglican and Anabaptist denominations. The Catholic Church eventually undertook its own Reformation, sometimes called Counter-Reformation because of its reactionary nature to the Protestant movements. The Catholic Church emerged from the Council of Trent a much more conservative institution, and continued to react negatively to society in a negative fashion for most of the next four hundred years. The Council of Trent (1545-63) sealed the divisions between the new Christian churches. A religiously unsettled Europe led to the Thirty Years War culminating with the Peace of Westphalia and the end of Papal control of the developing nation states.

1648-1789 The Age of Reason and Revival

The rise of rationalism and scientific thinking, with key figures such as Rene Descartes and Sir Isaac Newton provided major challenges to the Christian understanding of the world and its place in it. The Enlightenment, also known as the Age of Reason, was a time when man began to use his reason to discover the world, casting off the superstition and fear of the medieval world. The effort to discover the natural laws which governed the universe led to scientific, political and social advances. Enlightenment thinkers examined the rational basis of all beliefs and in the process rejected the authority of church and state. The mind becomes god; people begin to ask, "Who needs God?" Roman Catholicism responded to these major social changes in a defensive frame. During the Enlightenment, the concept of favoring individual liberty over the power of an institution became prevalent in France, Britain and the United States, leading to revolutions in two of those of those countries, as well as a concept of "basic human rights" that shaped the U.S. Constitution. The idea of religious freedom and tolerance also finds its roots in the Enlightenment and philosophers such as Voltaire and John Locke, who questioned religious doctrines. In France it led to Revolution.

1789-1914 The Age of Progress

Following the enlightenment of the mid-seventeenth to the eighteenth centuries and the French Revolution, founded on democratic ideals, the Church was on the defensive. Most modern ideas were seen as a threat. The nineteenth and twentieth centuries were a period of great advance for western culture, and much of the Church's agenda was centred on managing and dealing with these advances. The Syllabus of Errors, was published in 1864 by Pius IX, to refute a good many modern propositions as beyond reconciliation with the Church. The first Vatican Council (1870) promoted Papal Infallibility as a defense of the faith. The Industrial Revolution, which was a series of sweeping economic and social changes that created vast inequality, poverty and the middle class, was finally addressed by Pope Leo XIII in 1891 with his Rerum Novarum. This is often recalled as the beginning of Catholic Social Teaching. In emerging pluralist and totalitarian societies the relevance of Christianity was questioned by modernity.

1914-1965 The Age of World Wars

The two World Wars of the 20th Century forever changed the societal context in which Christianity found itself. The Catholic Church claimed neutrality in WWI (1914-18) and its gestures to bring about peace were largely ignored. The persecution of Christians following the Russian revolution justified the Catholic anti-communist stance ever since. After trying to avoid the war of 1939-45, The Vatican declared neutrality to avoid being drawn into the conflict. There was massive Vatican relief intervention for displaced persons, prisoners of war and needy civilians in Europe. Convents, monasteries, and the Vatican were used to hide Jews and others targeted by the Nazis for extermination. Many modern movements were atheist at heart: Karl Marx claimed religion to be the opiate of the people; Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, believed that God and religion were things that should be abandoned by the mature individual and culture in favour of science; Albert Camus, the French existentialist philosopher argued that religion is powerless to address the basic questions that face humankind. Faith, is seemed was under attack in the 20th Century. In the Catholic ghetto focused on Rome for solace against a difficult world.

1965 – The Church Emerging from Vatican II

For Catholics, the contemporary openness of the Church had its epoch in the Council of Vatican II. Pope John XXIII, considered as merely an interim Pope, was a man of vision who initiated the Council, which some claim was the most revolutionary event in the Church's history. Pope John XXIII said that the main purpose of Vatican II was aggiornamento, that is, bringing the church up to date. He called for the council to be "pastoral" in that it would define no new dogmas, but rather explore how the teaching of the church might be communicated more fully and put to use more effectively. His other principle was Ressoucement, a return to the scriptures and early fathers as sources for the renewal. The Catholic Church opened its windows to the world, and the radical changes begun at that time have repercussions still today. The modem Church continues to deal with internal processes of cleansing after acknowledging sexual abuse, injustice on a global scale, the impact of feminism and ecological degradation of the planet. The Church of the 21st Century remains focused on the person of Jesus Christ, the way, the truth and the life.